The term fungicide resistance, as used by FRAC, refers to an acquired, heritable reduction in sensitivity of a fungus to a specific anti-fungal agent (or fungicide). To manage resistance effectively, scientists study fungicide resistance on many different levels including the cellular, organismal or population/field level. Reports of "resistance" from the field (i.e. where growers observed reduced efficacy of a product that has been effective against that particular pathogen) must be confirmed by studies at the organismal level showing a reduction in sensitivity of the fungal isolate(s) to the specific fungicide. Some scientists use the terms reduced sensitivity or tolerance when referring to smaller reductions in sensitivity which may have little to no impact on fungicide usage in the field, and save the term "resistance" for large reductions in sensitivity of individual isolates which are likely to affect the efficacy of a specific fungicide under field conditions if the resistant isolates become widespread in the pathogen population. The term field resistance may also be used to indicate this loss of control under field conditions.

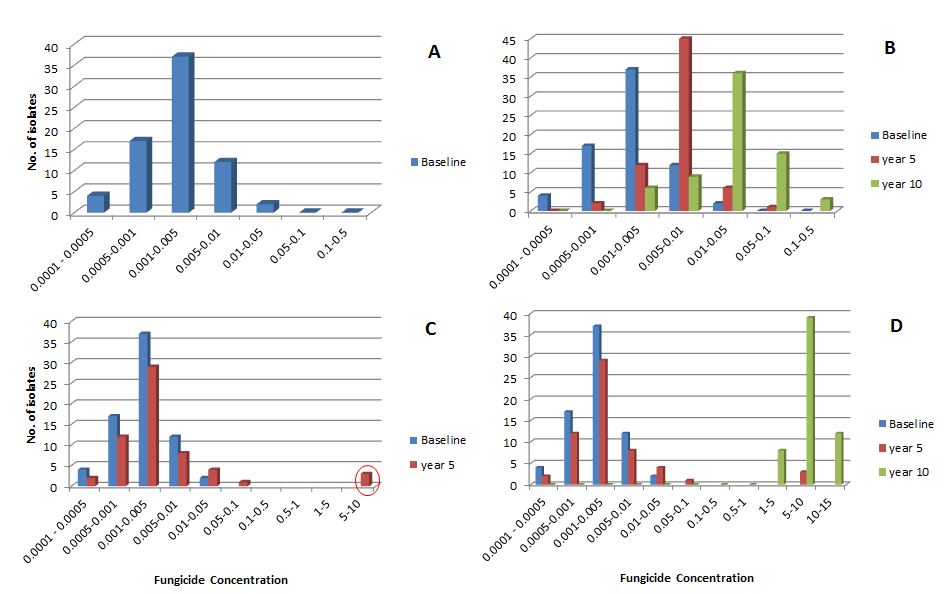

The development of fungicide resistance is a population evolutionary process. Fungi, like other organisms, are constantly changing. Occasionally, under certain conditions, these changes provide an advantage or disadvantage in terms of the progeny’s ability to survive and reproduce. Advantageous changes allow the individual containing the change to survive and reproduce resulting in their progeny constituting a greater percentage of the population over subsequent generations. This can happen relatively rapidly in fungi as their reproductive frequency (i.e. the number of progeny produced from a single individual and the speed with which they complete their life cycle) is high. For example, a single Phytophthora infestans lesion can produce thousands of spores and a spore can produce a new sporulating lesion in 3-5 days. The change may be evolutionarily neutral, or even slightly disadvantageous, under most conditions and only be advantageous when certain factors are present. This is the case with fungicide resistance. In most cases of fungicide resistance, the change leading to reduced sensitivity is evolutionarily neutral except when the specific fungicide is applied. The fungicide is exerting selection pressure on the pathogen population since it is killing the initial (or wild type) population but does not kill the changed (or mutant) population. When changes are slightly disadvantageous under normal conditions (i.e. in the absence of the fungicide), the frequency of the changed population may decrease when the selection pressure is removed. This disadvantage is termed a fitness penalty.